This post was written by Kate Oransky, a Petroleum Engineering Junior. Kate is also serving as secretary of the OU Student Chapter of the Society of Petroleum Engineers. This is a little about her internship experience with BP this summer.

A cubicle, one in series of rows, yellowing under the glow of fluorescent lights.

An oil rig, sitting in the Gulf of Mexico, surrounded by the ocean extending as far as the eye can see.

I worked in two vastly different environments during my internship with BP. I was a Subsea Wells Intern, supporting the Gulf of Mexico. Specifically, I was assigned to help with a new well that will be brought online later this year. At BP, the Subsea Wells team is in charge of subsea rig equipment specification, procurement, and execution.

In the office, my main project was to write a Statement of Requirements document (SoR) for a spanner joint. A spanner joint is a safety-critical piece of equipment. It is used to install the upper completion equipment and interfaces with the Blow-Out Preventer (BOP), which is the most important piece of equipment in a well. The spanner joint interfaces with many other pieces of equipment as well, including the tubing hanger running tool and landing string. It also must be compatible with the completion fluid. Thus, one of my responsibilities was to reach out to other BP teams as well as service companies (e.g. Halliburton) for pertinent information necessary to design the spanner joint. I was also responsible for reviewing API safety standards and BP guidance documents, referencing all applicable standards in the SoR. This ensures the finished spanner joint will meet all compliance and safety regulations. Attention to detail and safety considerations guarantee the SoR completely and clearly covers all information the vendor needs to design the spanner joint. I also wrote another SoR for an Installation Workover Control System (IWOCS), visited multiple equipment vendor sites, examined hours of underwater Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) footage and travelled offshore.

I went offshore to the West Auriga drill ship, which was working in BP’s Atlantis field. To get there, I flew from Houston to New Orleans in an airplane, then drove to Houma, Louisiana in a rental car. From Houma, I took a 90 minute helicopter flight before making a smooth landing on the helideck of the West Auriga.

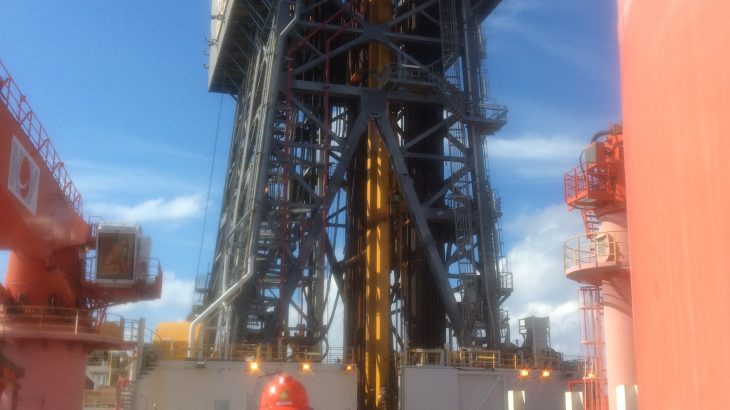

This is a picture of me in front of the derrick of the West Auriga. I was quite surprised by how massive everything was offshore. This picture provides some sense of the scale of the derrick.

This is a picture of me in front of the derrick of the West Auriga. I was quite surprised by how massive everything was offshore. This picture provides some sense of the scale of the derrick.

Weeks before my trip, I had to complete Helicopter Underwater Escape Training (HUET), to get certified for flight on the helicopter. In this training, you sit inside a giant tube designed somewhat like a helicopter; it has seats with standard safety belts, and windows next to each seat. Then, after you get in and buckle up, they suspend the tube over the water, and drop you Tower-of-Terror style into the pool. Except here, you flip over upside down, underwater, and push out the “helicopter’s” window to escape. This training requires one to be dropped in the pool FOUR times: twice right-side up, twice upside-down!

I was on the drillship for a few days, and witnessed subsea procedures being executed. For example, I was present inside the drill shack while the drill crew and team were running tools and equipment downhole. I observed the team’s attempt to latch the tool to the tubing hanger, and watched their troublesho oting efforts when the tool failed to latch properly. I also observed the team running a crown plug pulling tool on slickline; and talked to the men running the slickline unit to learn about what hanging weights they were looking for and what that meant. While out there, I supported the BP Subsea team and helped make sure the team was following subsea procedures.

oting efforts when the tool failed to latch properly. I also observed the team running a crown plug pulling tool on slickline; and talked to the men running the slickline unit to learn about what hanging weights they were looking for and what that meant. While out there, I supported the BP Subsea team and helped make sure the team was following subsea procedures.

Throughout my internship, I learned a great deal about subsea equipment, and how it controls the flow as hydrocarbons are brought to surface. My experiences both onshore and off taught me a lot about deepwater production of hydrocarbons and the time and effort that goes into designing the equipment, every step of the way. I can now easily transition to another deepwater wells role with a strong basis of understanding of the equipment needed and the processes required to get the oil to surface. I’ll never forget the amazing opportunities and experiences I had this summer.

The West Auriga’s spare Blow-Out Preventer (BOP) is pictured here. The West Auriga has another BOP just like this one, but it’s thousands of feet below sea level.